Did the FBI use the MyHeritage database?

The FBI might have used the MyHeritage database to identify Kohberger as a suspect. This would be a violation of the database's terms and conditions.

I am still drafting my post about the investigative genetic genealogy (IGG) process among other things, but not quickly enough to keep up with the speed of this court case, so I will post this particular explanation now. My research on this issue began after a conversation on Reddit with the host of the podcast DNA:ID.

The IGG process can be broadly divided into two parts: The creation in the lab of the suspect’s SNP profile extracted from the suspect’s DNA sample found at the crime scene, and the construction of the family tree based on that SNP profile and the genetic matches in the genetic genealogy databases.

At the beginning of the IGG process in this case, Othram Labs was under the impression that it would conduct both the creation of the SNP profile and the genetic genealogy; however, just as Othram began the construction of the family tree, the FBI took over.

According to the state’s motion for a protective order of the IGG information:

Law enforcement found the DNA of a potential suspect at the crime scene, and the FBI submitted the DNA to one or more publicly available genetic genealogy services to determine potential relatives of the suspect. The FBI then used common genealogical techniques to develop a family tree leading to Defendant.

What the State’s argument asks this Court and Mr. Kohberger to assume is that the DNA on the sheath was placed there by Mr. Kohberger, and not someone else during an investigation that spans hundreds of members of law enforcement and apparently at least one lab the State refuses to name…

Frankly, the fact that members of the FBI are so concerned about permitting Mr. Kohberger to know what they were up to with what was supposedly his DNA, does not give one the impression that there is “nothing to see here” as the State seems to imply.

The fact that the FBI took over the IGG process is notable: Othram’s genealogists are more than capable of constructing the family tree on their own, so the FBI’s interception was not due to a disparity in skill between genealogists.

The FBI likely took over the process for another reason; perhaps, they were unsatisfied with the genetic matches produced by Othram and wanted to use a database that Othram won’t touch.

The Databases

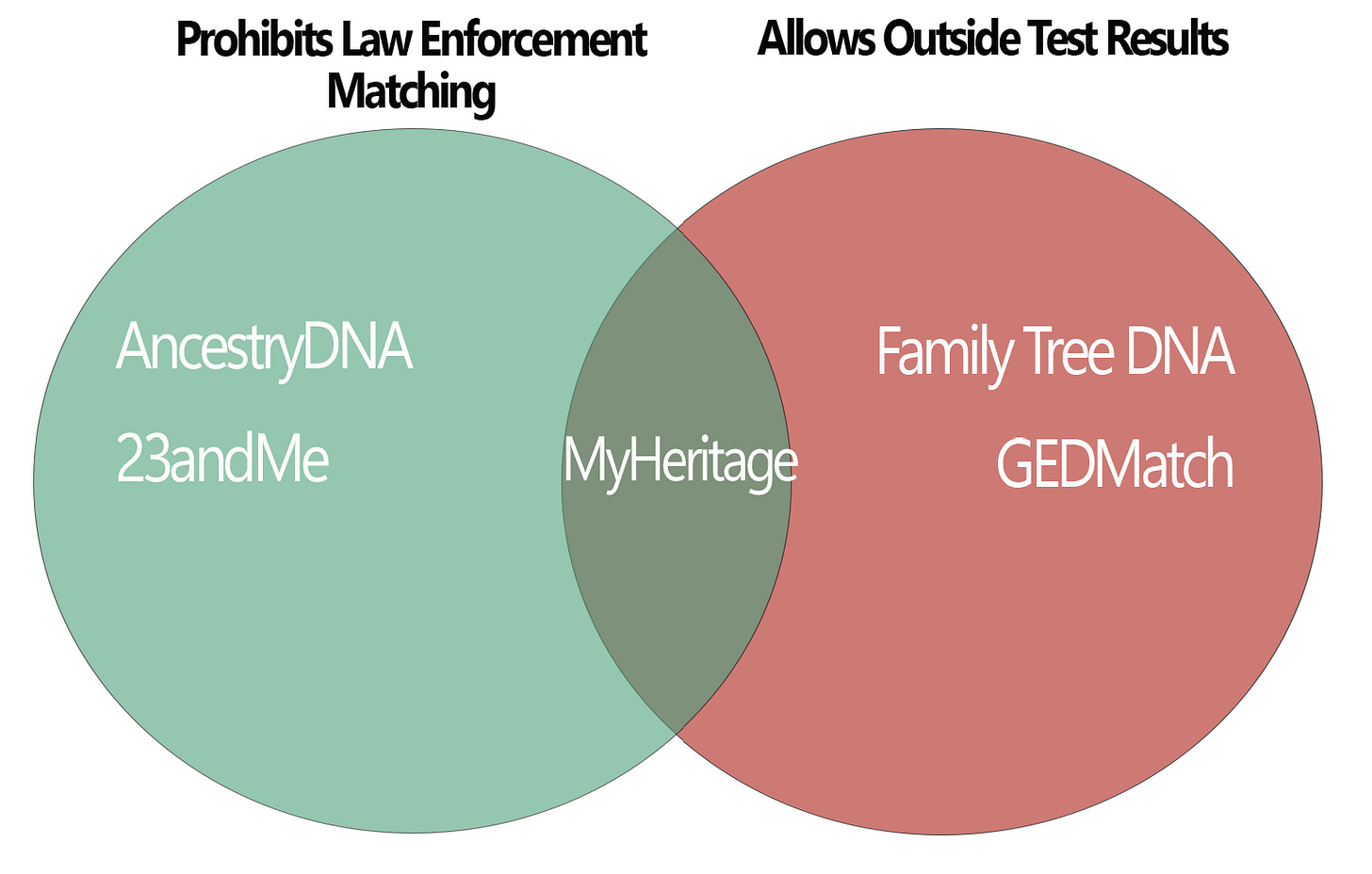

There are five genealogical databases relevant to this discussion: (1) AncestryDNA; (2) 23andMe; (3) MyHeritage; (4) GEDMatch; and (5) Family Tree DNA. (DNASolves, which is owned by Othram, and DNA Justice are dedicated exclusively to IGG and are not meant for genealogy hobbyists; however, these databases are very small and were likely not useful in identifying Kohberger as a suspect.)

The companies that allow law enforcement to mine their databases for genetic matches—a process referred to as law enforcement matching—are GEDMatch and Family Tree DNA. The other three companies bar law enforcement matching entirely.

Moreover, AncestryDNA and 23andMe require consumers to take the company’s own DNA kit to submit for analysis; one cannot submit the computer file extracted from one company’s DNA test to a different company. This means that if investigators wanted either company to analyze a suspect’s DNA, then they would need to submit a sufficient saliva sample to the company’s lab and create a fictitious user account for that DNA sample. There are a few reasons why this would be unreasonable.

The other three companies—MyHeritage, GEDMatch, and Family Tree DNA—allow users to upload files extracted from other tests. This means that one could take a test through AncestryDNA, download the .txt file from the Ancestry website after the completion of the testing, and upload that file to another permitting database.

So taken altogether, there is only one database that both (1) prohibits law enforcement matching, and (2) allows computer files extracted from outside tests.

That database is MyHeritage.

The MyHeritage Terms and Conditions

MyHeritage Ltd. aims to protect the privacy of its consumers by expressly barring law enforcement from using their database to identify victims and suspects. According to the MyHeritage website:

[U]sing the DNA Services for law enforcement purposes, forensic examinations, criminal investigations, "cold case" investigations, identification of unknown deceased people, location of relatives of deceased people using cadaver DNA, and/or all similar purposes, is strictly prohibited, unless a court order is obtained. It is our policy to resist law enforcement inquiries to protect the privacy of our customers.

But the terms and conditions is an honor system. While MyHeritage Ltd. would have grounds to sue a law enforcement entity for breach of contract if investigators were to use the database to identify a suspect, the technology is still there, and tenacious investigators hoping to identify a suspect could throw caution to the wind and use the database anyway.

And they have in the past.

State of Minnesota v. Jerry Arnold Westrom (2019)

Jerry Arnold Westrom was charged and ultimately convicted of a homicide that occurred in 1993. Investigators collected the unidentified suspect’s DNA at the crime scene, and 26 years later, FBI agents input that DNA profile into MyHeritage and Westrom was arrested.

This move violated the MyHeritage terms and conditions, and Westrom’s attorneys filed a motion to suppress the evidence on that basis. According to the defense:

Mr. Westrom has a reasonable expectation of privacy in his genetic information on the genetic genealogy website MyHeritage. Law enforcement violated Mr. Westrom’s reasonable expectation of privacy by accessing his genetic information on MyHeritage. Law enforcement did not have a warrant or voluntary consent to search Mr. Westrom’s genetic information…

The testing and analysis of Mr. Westrom’s DNA invaded his expectation of privacy in his private genetic information and therefore was a search for Fourth Amendment and Article 1, § 10 purposes…

But there’s a problem with the defense’s argument: Westrom’s DNA profile was not in the database; therefore, it was never accessed. By genetic information, the defense is really referring to the shared data between users that formed the links in the investigative chain leading to Westrom.

In genetic genealogy databases, users can view their genetic matches and metrics indicating shared DNA. Below is an example of the metrics in MyHeritage listing the shared DNA between the user and one of their matches.

Allow me to explain the difference between a DNA profile and metrics of shared DNA between persons by way of analogy.

Suppose my friend confesses a crime to me via text message. I can freely show this text message to law enforcement; an officer would not need a search warrant to look at my screen. He would, however, need a search warrant to pull my friend’s cellular data to retrieve the raw text message. For the purposes of this analogy, the text message as seen on my phone could be viewed as shared data between persons.

Likewise, as the courts have ruled thus far, law enforcement doesn’t need a warrant to view the shared metrics between a genetic genealogy database user and a suspect’s DNA profile; that said, an officer needs a search warrant to collect an arrestees DNA with a buccal swab. (Privacy activists argue that the law should require the police to request a warrant for the creation of the SNP profile from the suspect’s DNA, and this appears to be where the tide will eventually turn.)

In the order denying the motion to suppress in the Westrom case, the court ruled:

Defendant provided no authority for the argument that society has recognized, as reasonable, a privacy interest in the gathering of naturally shed and discarded genetic material and its analysis for identification purposes…

Because of the foregoing, Defendant therefore also does not have a legitimate expectation of privacy in his identifying information contained within the DNA of his family members. If Defendant does not have an expectation of privacy in his own genetic identifying information, there seems no reason to find that Defendant would somehow have a greater expectation of privacy in the identification information shared with other people.

(Emphasis mine.)

The flaw in the defense’s argument is that the genetic information is not only Westrom’s genetic information; it falls within the overlap of multiple domains, a space where nobody with that shared genetic information has an expectation of privacy.

In addition, there is case law outlining who is in the position to complain about what in the courts, and thus far the courts have ruled that a defendant is not entitled to dispute evidence based on an identification through IGG.

The Defendant Didn’t Have Standing

The concept of standing is so foundational that a shift in its definitional criteria could trigger chaos in the system. According to the United States Supreme Court, “In essence the question of standing is whether the litigant is entitled to have the court decide the merits of the dispute or of particular issues.” If a defendant does not have standing, then the argument for a motion to suppress the evidence fails.

The court in the Westrom case ruled that Westrom did not have standing to assert a violation of his Fourth Amendment rights based on the FBI’s use of the MyHeritage database. The court stated, “Law enforcement’s possible violation of MyHeritage’s service agreement may subject them to action from MyHeritage, but the Court does not see any reason why this violation of a private company’s terms would implicate constitutional protections.” In other words, MyHeritage might have standing in a civil suit against the FBI, but Westrom has no standing to dispute the evidence in his criminal case.

So why didn’t MyHeritage sue the FBI for using their database to successfully catch a man who stabbed a woman to death in her bed? Well, the answer is in the question: It would be bad optics, as they say. And the same goes for a case involving a man accused of stabbing four college students to death.

And now we’re back to the court case whence we came.

State of Idaho v. Bryan C. Kohberger (2022)

If you are wondering how this will play out in the Kohberger case, then you are in luck, because I can predict the future. If it’s true that the FBI used the MyHeritage database to catch Kohberger as a suspect—and I’m placing the odds at close to 90% at this point, or the odds of the FBI using a backdoor of some kind at 100%—then the defense will file a motion to suppress the evidence. That motion will be denied on the grounds that the defendant lacks standing. MyHeritage Ltd. won’t sue the FBI because the company might look bad taking a legal stance sympathetic to someone who, by all appearances, stalked a young woman for months before murdering her and her friends.

And once that motion is denied, we can then all move on and the case will progress smoothly from here on out. Right?

…

Right?!

Here we are, 1 year later. Courts docs unsealed.

Looks like you nailed it.

There’s another famous case that used MyHeritage, in violation of its terms of service: the Golden State Killer case - the case where IGG was first used in a criminal case. (Note, the legality of the IGG was never contested up in that case - I’m guessing because the defense figured it might lose that battle, as Westrom did, plus the prosecution was willing to negotiate the death penalty.)

For that case’s IGG, the team Paul Holes put together, which included himself, were new to IGG, but they had as their advisor IGG expert Barbara Rae Venter (experienced in DNA Doe cases, not criminal cases at that point.) The team had tried GEDMatch and FamilyTreeDNA but could only get to third cousin matches and were thrashing until...

Here’s Paul Holes description of how the process was going from his autobiographical book, “Unmasked: My Life Solving America’s Cold Cases,” from Chapter 25, “Joseph James Deangelo” - though he never mentions the MyHeritage terms of service violation:

“The trees grew to be huge. At one point we were researching sixty possible distant relatives and tracing their family trees all the way back to the 1700s. The closest we came was third cousins, more than a dozen, which wouldn’t bring us close enough for a manageable search. We were all getting frustrated. In February 2018, Barbara emailed Kramer and me. “We may have just caught a break.” She had used her personal account on MyHeritage.com and found a second cousin to the Golden State Killer. We were one generation closer and a giant step further in the search.”

Excerpt From

Unmasked

Paul Holes

https://books.apple.com/us/book/unmasked/id1586643024